Nor is the definition of a ‘population' obvious: one can expand or contract the size of the group almost at will ( Marks, 2008). Geographical isolation scarcely exists today, and even in humanity's past it became commonplace that ‘genes travel along roads'.

However, it is hard to apply such definitions to humans.

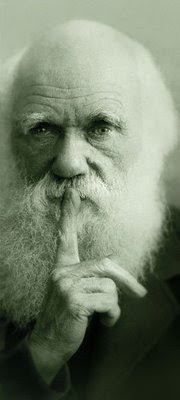

For biologists, the definition is, at first sight, reasonably clear: a race is an interbreeding, usually geographically isolated population of organisms differing from other populations of the same species in the frequency of hereditary traits. Instead, I want to reflect on the impossible tangles that we have got ourselves into in attempting to reconcile three uses of the term ‘race': the popular usage, that used by the social sciences, and that of biologists. My response to this likened asking such questions about group differences in intelligence to research on phlogiston in an era of modern chemistry ( Rose, 2009), and I do not wish to reprise those arguments here. A recent essay in Nature even argues that it is time to re-open the ‘untouchable' question of racial and gender differences in intelligence-or rather, its ostensible surrogate measure, IQ ( Ceci & Williams, 2009). And there are small but robust differences, chemically and anatomically, between the brains of men and women, although nobody has any real idea what the implications might be. Distinct population groups-not races in the biological sense-do, after all, show reliable variations in gene frequencies, some of which are associated with known disorders such as Tay–Sachs disease or cystic fibrosis. The biological sciences are becoming re-racialized and re-sexed. During the 150 years since Darwin wrote such views on race, gender and eugenics, whilst sometimes subterranean, they have never entirely vanished a sorry history, often told.Ĭurrent developments in both genetics and neuroscience are raising them again, however, clothed in modern language. He enthusiastically endorsed his cousin Francis Galton's view of hereditary genius transmitted down the male line, and nodded cautiously towards eugenics. Although female choice explains sexual selection, it is the males who evolve in order to meet the chosen criteria of strength and power such nineteenth century differentiation between the sexes was crucial in providing an alleged biological basis for the superiority of the male.Īny attempt to separate a ‘good' Darwin from a ‘bad' Social Darwinist cannot be sustained against a careful reading of Darwin's own writing. His brain is absolutely larger the formation of her skull is said to be intermediate between the child and the man” ( Darwin 1871). He stated that the result of sexual selection is for men to be, “more courageous, pugnacious and energetic than woman a more inventive genius. Darwin's views on gender, too, were utterly conventional. He was also convinced that evolution was progressive, and that the white races-especially the Europeans-were evolutionarily more advanced than the black races, thus establishing race differences and a racial hierarchy.

True, he was committed to a monogenic, rather than the prevailing polygenic, view of human origins, but he still divided humanity into distinct races according to differences in skin, eye or hair colour. It is a nice try, but it does not convince me Thomas Malthus and the Galapagos finches provide a much more plausible origin for the theory of evolution by natural selection.ĭarwin was, after all, a man of his time, class and society. Among the spate of books published on this occasion, one actually stands out in its novelty: the claim that Darwin's evolutionary theory was inspired by his hatred of slavery, as especially experienced during his epic Beagle voyage ( Desmond & Moore, 2009).

#CHARLES DARWIN TV#

Given all the celebrations, conferences, special issues and TV programmes, everyone must know by now that it is 200 years since Charles Darwin was born and 150 years since the publication of The Origin of Species ( 1859).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)